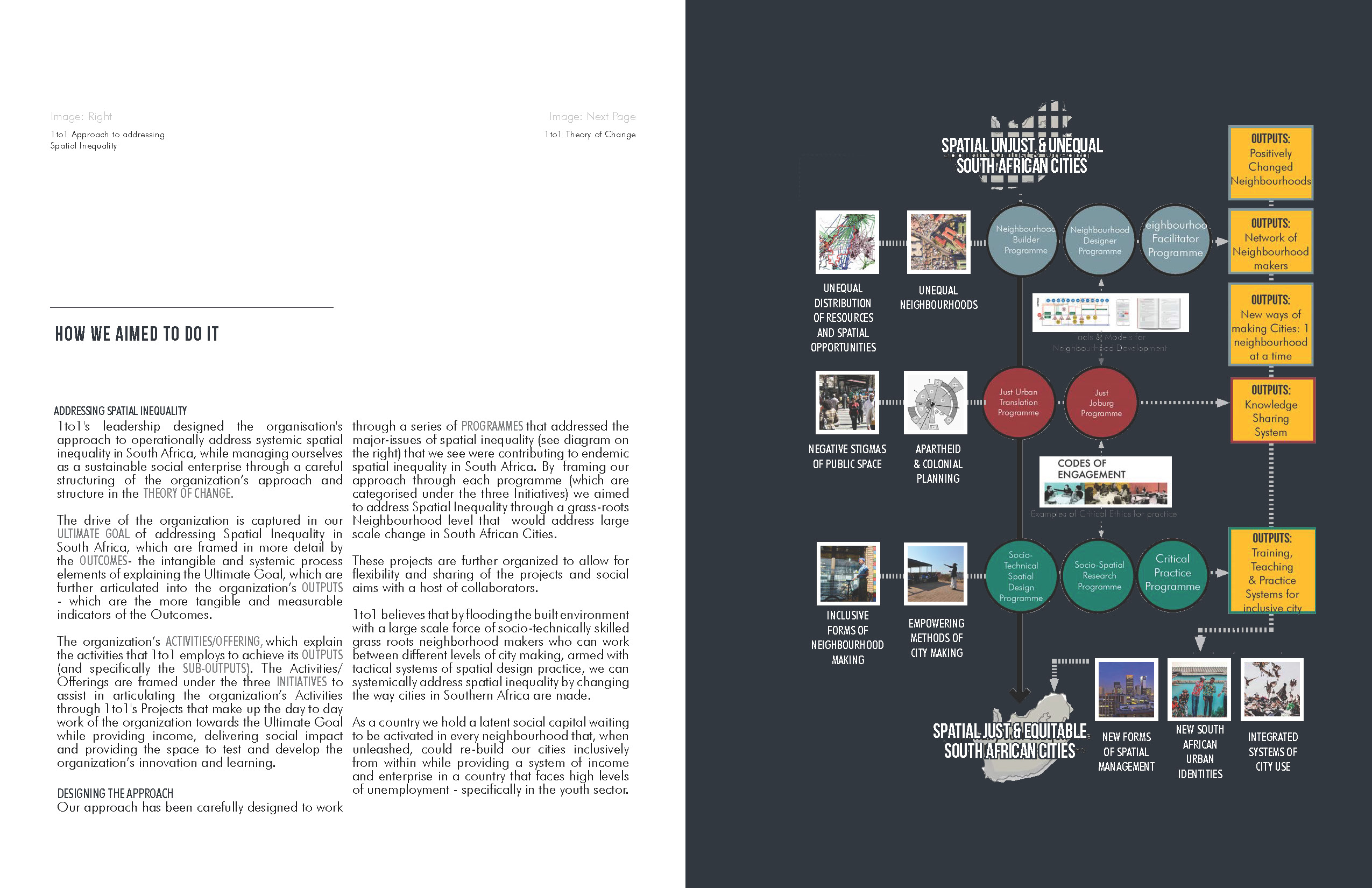

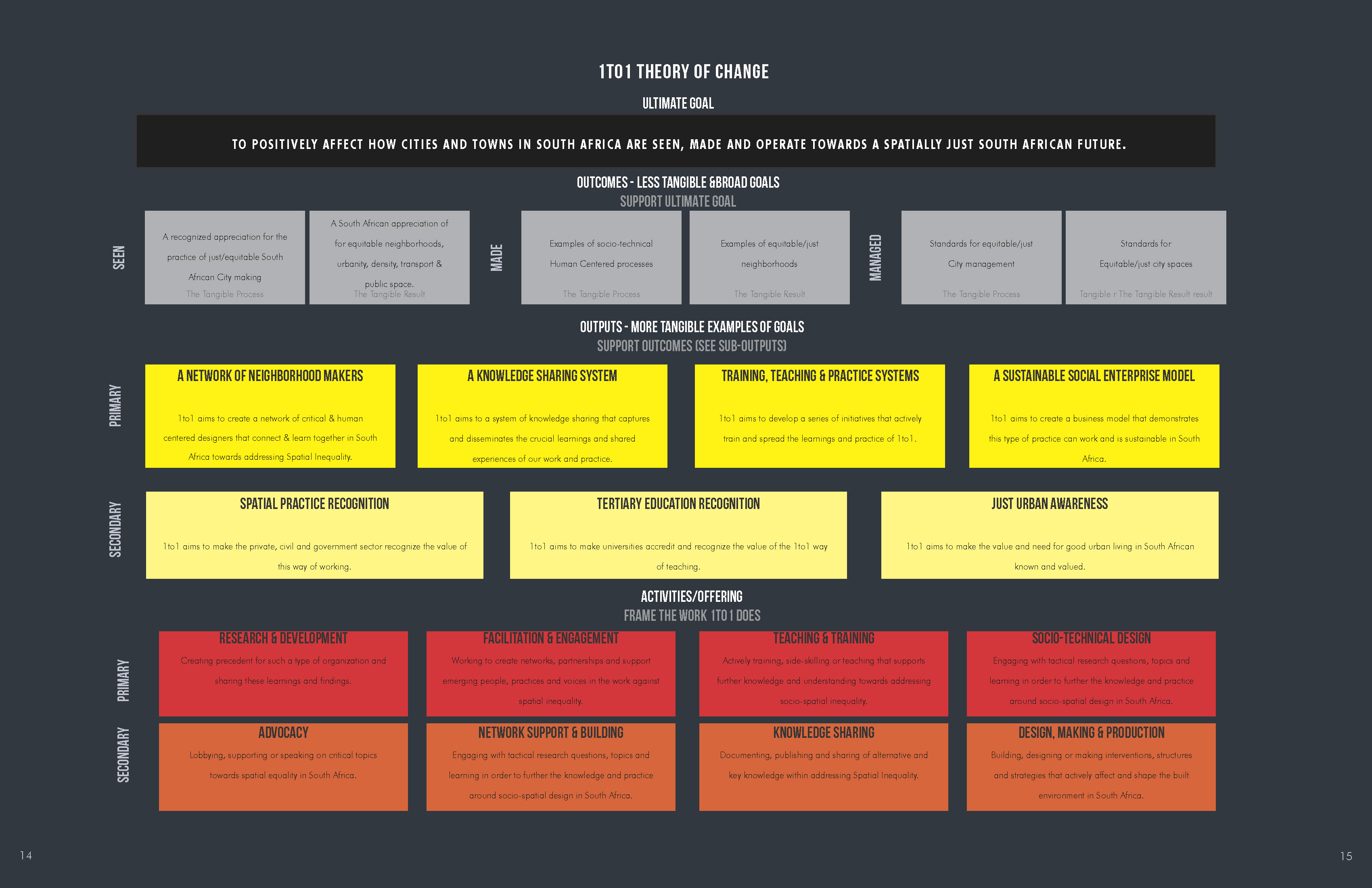

Through 1to1 I have been very fortuante to be a part of this global network project. The Initaitve was held over 3 years and supported research, learning and engagements across South Africa, Zimbabwe, Kenya and Manchester, United Kingdom.

See: https://www.gdi.manchester.ac.uk/research/groups/global-urban-futures/scaling-up-participation-in-urban-planning/ for all details. Summary below:

Goal:

In recent decades the world has experienced unprecedented urban growth. According to the United Nations 4 billion people, or 54% of the world’s population, lived in towns and cities in 2015. That number is expected to increase to 5 billion by 2030.

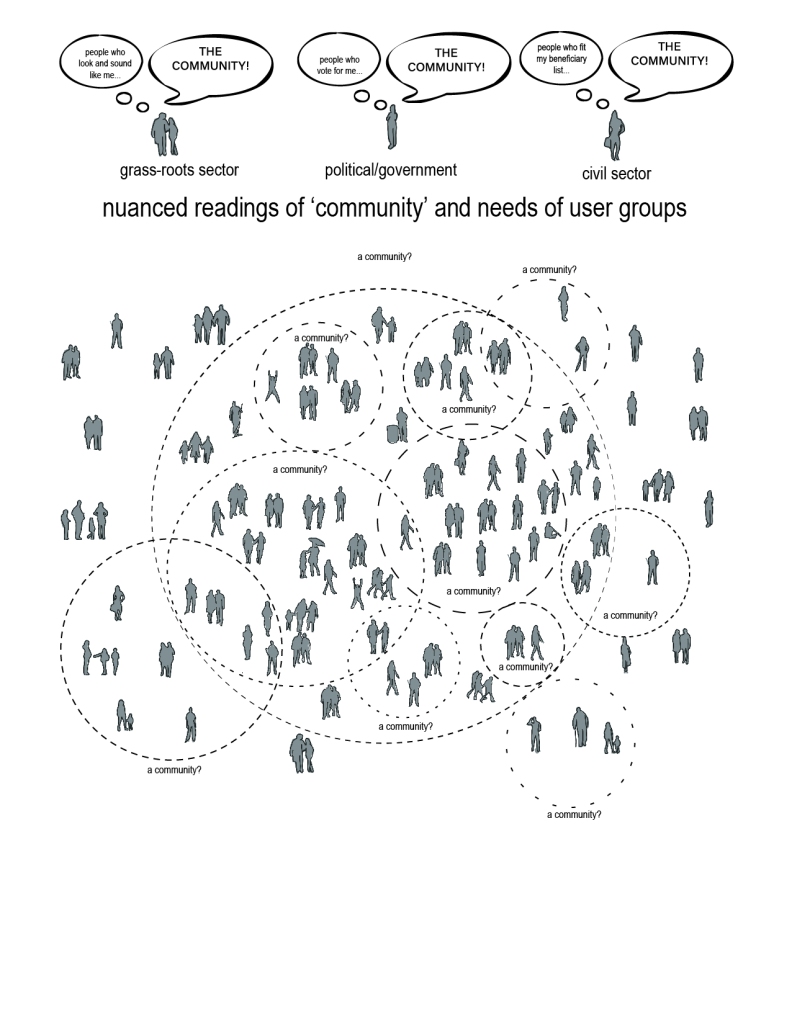

Urban growth has outpaced the ability of many governments to build infrastructure and, in many towns and cities in the global South, provision for housing is inadequate. Consequently one in three urban dwellers live in informal settlements. Issues of insecure tenure, poor access to basic services, and insecure livelihoods are all prevalent. Although local government may have the desire to improve the situation they are, in many cases, under-capitalised and under-capacitated. Existing planning legislation and practices remain incapable of resolving such issues therefore local residents try and resolve these themselves. Their efforts are, however, fragmented and localised.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the resulting Sustainable Development Goals vow to end poverty, to achieve gender equality and ensure liveable cities. Multi-disciplinary approaches that build on local action and create strong partnerships are needed in order to advance initiatives and to address the UN Sustainable Development Goals to ensure the availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all and to make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.

This commitment to ‘leave no-one behind’ highlights the importance and strengthens the significance of citizen involvement in urban development. Academics seek to contribute to new solutions and approaches to problems faced by the residents in informal settlements. Universities have an important role in generating, analysing and monitoring data that can be used by policy makers. However this should be done in collaboration with local government, local residents and organisations. Citizen involvement and public participation in policy-making and programming should be nurtured and encouraged.

Aims and objectives:

The network aims to develop the knowledge required to move from participatory community-led neighbourhood planning to city-scale planning processes. The aims and objectives of the project are critical to achieving inclusive urban futures, these include:

-Develop frameworks that build on effective approaches of community-led planning for informal settlement, upgrading at the neighbourhood level, and then scaling these to the city level.

-Locate these frameworks within traditions of alternative planning including participatory co-productive planning, participatory planning and action planning thus strengthening the critical mass of people-centred approaches supporting inclusive urban development. This component will elaborate why grassroots organisations make a substantive contribution to inclusive urban development and the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals.

-Develop a framework that enables the integration of community understandings and innovations with academic and professional knowledge.

-Achieving these objectives requires a combined effort from academics and civil society agencies. While academic researchers encourage civil society agencies to engage meaningfully and substantively, it is difficult to achieve this within academic research programmes. By creating a formal network the opportunity for engagement is created, to deliver on a set of shared objectives and to achieve the strengthening of relations between individuals and agencies.

The network:

Professor Diana Mitlin, Managing Director of the Global Development Institute at The University of Manchester, is the project lead.

Dr Philipp Horn, Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Manchester’s School of Education, Environment and Development and Postdoctoral Research Associate at The Open University, provides research support to the project.

The network is a co-productive knowledge partnership between civil society action research agencies and academic departments. The project combines professionals and academics with a commitment to substantive change and experience at local level.

This network is funded by the Leverhulme Trust.

SDI-affiliated civil society alliances of organised groups of low-income residents are working in partnership with academic institutions. Their participatory efforts at neighbourhoods have been presented as best-practice examples in urban poverty reduction. These alliances are:

Dialogue on Shelter Trust, Zimbabwe

Slum Dwellers International Alliance, Kenya

The network comprises committed partners that have been directly involved in previous participatory planning processes, these include:

The University of Manchester (UK)

The Faculty of Art Design and Architecture at the University of Johannesburg (South Africa)

CURI at The University of Nairobi

Faculty of the Built Environment at the National University of Science and Technology (Zimbabwe)

Design Society Development DESIS Lab based at Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture (FADA), The University of Johannesburg

1to1 – Agency of Engagement

All of these departments have a track record on urban development planning. The selected individuals within these departments have established connections with low-income communities, planners and urban professionals within their respective countries as well as sub-Saharan Africa. They have previously conducted practice relevant research around topics such as informal settlement upgrading, service provisioning and participatory community planning.

See: https://www.gdi.manchester.ac.uk/research/groups/global-urban-futures/scaling-up-participation-in-urban-planning/ for all details.